During the French Revolution, ideas and events influenced women to break from the conformities of their society and fight for their civil rights.

Assess the validity of the above statement, discussing the influences and views of men that pushed women to "break" from traditions and how this affected their roles in revolutionary French society.

Document 1

-Madame, is this where Monsieur Rousseau

lives.... Could I speak to him in person?.... I came to fetch an answer

to a letter I wrote him several days ago.

-Mademoiselle, you cannot speak to him, but you can tell the

people who made you write, for surely it is not you who wrote a letter

like that....

-I beg your pardon....

-Why, the handwriting alone shows that it is from a man.... All I

can tell you is that my husband has absolutely renounced everything; he

would like to be of service, but he is old enough to be entitled rest.

-I know, but at least I should have felt honored to have received

his message from him personally. I would have taken advantade fo this

opportunity to present my homage to the man I esteem the most in the

world. Please, accept it in his stead, Madame.

Dialogue between Mlle. Manon and Mme. Rousseau, 1770

Document 2

You have to be a mother and have heard your children ask for bread you cannot give them to know the level of despair to which this misfortune can bring you…. With children who are hungry and who ask repeatedly and tearfully for food--it seems as if each sound issuing from their chests parched by poverty is the point of a dagger striking their mother's heart. She cannot bear it, and her pain makes her capable of doing anything because she sees nothing, feels nothing, except the imperious law of nature commanding her not to let those perish who owe her their birth.

Elisabeth Guenard, Historical Memoirs of Madame Marie-Therese-Louise de Carignan, Princess of Lamballe, 1789

Document 3

March of Women on Versailles, October 1789

Document 4

-What a shame that the ministry should be spoiled by such a man! Where on earth did you find him?

-What can we do, he is at the head of a party of barkers. If he

wasn't made part of the machinery, he would turn against it, and

besides, he has served the Revolution and can be useful to it.

-I doubt it, and your policy strikes me as detestable.... It is

better to have one's enemy on the outside than within. Besides, a man

who seeks only his private advantage will always be the enemy of the

public good.

-This is no reason. People like him need a position and means.

Satisfy their ambition and they are your creatures. Besides, Danton has

wit and can discuss things pleasantly. He will work out for the best.

-I wish it and don't want to prejudge him because I don't know

him. But since you are my good friends, let me tell you frankly that in

politics you reason like little boys.

Political dialogue between Mme. Roland and her Girondist friends, 1792

Document 5

"Contending for the rights of women, my main arguement is built on this simple principle, that if she be not prepared by education to become the companion of man, she will stop the progress of knowledge and virtue...And how can woman be expected to co-operate unless she knows why to be virtuous? unless freedom strengthens her reason till she comprehends her duty, and sees in what manner it is connected with her real good. If children are top be educated to understand the true principle of patriotism, their mother must be a patriot; and the love of mankind, from which an orderly train of virtues spring,can only be produced be considering the moral and civil interest of mankind; but the education and situation of women at present shuts her out from such investigations...and I have contended, that to render the human body and mind more perfect, chastity must more universally prevail, and that chastity will never be respected in the male world till the person of a woman is not, as it were, idolised, when little virtue or sense embellish it with the grand traces of mental beauty, or the interesting simplicity of affection..."

A Vindication of the Rights of Women, Mary Wollstonecraft, a British author, addressing the author of a proposed new constitution for France, 1792

Document 6

"Let us arm ourselves...Let us show men that we are not inferiors in courage or in virtue...Let us rise to the level of our destinies and break our chains; it is high time that women emerged from the shameful state of nullity and ignorance to which the arrogance and injustice of men have so long condemned them. Let us return to the days when the women of Gaul debated with men in public assemblies, and fought side by side with their husbands against the members of liberty. Our conduct at Versailles on October 5 and 6 and numerous decisive and important occasions since proves that we are not strangers to noble and magnanimous sentiments...Why should we not compete with men? Do they alone deserve glory? We too wish to gain a civic crown and claim the right to die for liberty, a liberty perhaps still dearer to us since our sufferings under despotism have been greater."

Theroigne de Mericourt, addressing the fraternal club of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, March 25, 1792

Document 7

"It is horrible, it is contrary to all the laws of nature for a woman to want to make herself a man...Since when is it decent to see women abandoning the pious cares of their households, the cribs of their children, to come to public places to harangue in the galleries?...Impudent women, who want to become men, aren't you well enough provided for? What else do you need? Your despotism is the only one our strength cannot resist, since it is the despotism of love, and consequently, the work of nature, remain what you are; far from envying us the perils of a stormy life, be content to make us forget them in the heart of our families, in resting our eyes on the enchanting spectacle of our children made happy by your cares."

Pierre Chaumette, chairperson of the Council of the Paris Commune, in response of women's protest and use of bonnets rouge, 1793

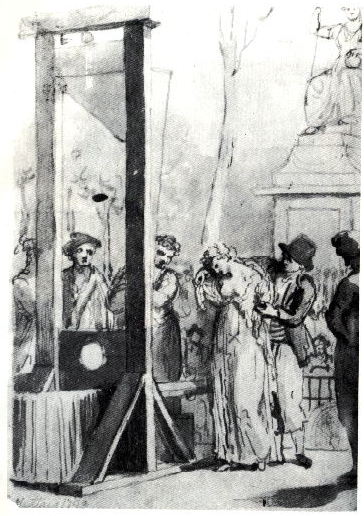

Document 8

Women Guillotined, 1794

Document 9

.... Mothers, daughters, sisters and representatives of the nation demand to be constituted into a national assembly. Believing that ignorance, omission, or scorn for the rights of woman are the only causes of public misfortunes and of the corruption of the governments, the women have resolved to set forth in a solemn declaration the natural, inalienable, and sacred rights of woman in order that this declaration,...., will ceaselessly remind them of their rights and duties....

Olympe de Gouges, Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen, 1791

Please write your answer below the double line.

The Enlightenment of 18th century Europe demonstrated the massive developments that had evolved from previous eras. Philosophers like Rousseau, Voltaire, Humes, and Locke had risen from obscurity to appeal to many contemporary thinkers of the time with ideals of reason, ethics, and freedom. Yet despite these vast improvements numerous gaps would have to be filled to pace the judicious proclamations of the Enlightenment with that of 21st century society. Though democratic ideals were extensively publicized during the time, such inherent benefits were singularly appropriated for men. The majority of writers during the Enlightenment maintained traditional views of women, relegating them to roles of domesticity and household affairs. Tableaus for female positions from even contemporary males of the 18th century could typically be summed up in Rousseau’s book Emile. Keeping with the notions of the Enlightenment, Emile considers the education of women in society, as dully emphasized on matronly roles with little necessity for politics or acute intellect. Such views that had been tirelessly thrusted upon female society in a generation where democracy and rationale supposedly reigned supreme, had long taken its toll on ranks of women belonging to both the nobility and peasantry. The most apparent events of feminine uproar during the time could be found in late 18th century France, where the events of the French Revolution incited women to take an active role in public affairs. The nationwide problems called for the most vociferous of male citizenry, but had neglected the issues and grievances of female citizenry. Though the revolutionary climate afforded French women the opportunity to articulate their political rights in the form of pamphlets, petitions, and commissions prevailing ideas of female frivolity strictly consigned women to marital status and obdurately repressed them where political associations were concerned.

Societal beliefs that supported female roles as mothers and wives, had acted as a method to uphold as well as restrain women. While women during the French revolution were working to contest such impeding views, they used these same views to buttress their political and social ambitions. Utilizing such stigmatizing views as a call to action, women also associated these views in a softer light necessitating additional civil liberties. When responding to a letter authored by Mademoiselle Manon to he husband, Madame Rousseau insists, “[You] can tell the people who made you write, for surely, it is not you who wrote a letter like that…it is from a man” [Document 1], virtually invalidating any claims that women could be equal to men in the public sphere and further promoting ideals that women were intellectual inferior to men. Such assumptions were undoubtedly amplified further in society and propelled women to take action in revolutionary France. However, when referencing political objectives French women substantiated their claims with matronly roles. Marie de Carignan asserts “You have to be a mother…the imperious law of nature commanding her not to let those perish who owe her birth,” [Document 2] to reinforce women challenging natural roles during the March on Versailles, to feed their starving children. Furthermore, Mary Wollstencraft imperiously asserted that virtuous women must be equitably educated to serve the “moral and civil interest of mankind” [Document 5], once again utilizing societal constructs to enforce female egalitarianism.

Although many women modeled many of their

political gains within the limits of conventional thought, still others

directly attacked traditional roles and confidently participated in

French politics. Theroigne de Mericourt addressed males with the

affirmation that “…women emerged from the shameful state of nullity and

ignorance to which…men have so long condemned them [Document 6].

Parisian women in the Fall of 1789 disposed of subservient roles when

they angrily marched to Versailles to confront the King and demand a

proper accounting of the high prices of bread [Document 3]. In the

years following the Fall of Bastille, women found themselves in more

formidable areas of politics, in which they openly critiqued France’s

male leaders [Document 4] and contested the justifications of male

civilities with equal conviction for female rights.

The boldest political statements were made by Olympe de Gouges

when she bitterly criticizes gender inequities in the Declaration of

the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen modeled after the

Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. In her publication she

states “Believing that ignorance, omission, and scorn for the rights of

woman …[cause] public misfortune and corruption of government…”

[Document 9], and in doing so declares the inalienable rights granted

to women, despite their positions as virtuous mothers or nefarious

courtesans.

Unfortunately the civic passion aroused by the notorious gains that French women had made in the political sphere, would be short-lived as Jacobin rule assumed authority. As France’s already precarious political situation grew more turbulent based on the suspicions of the revolutionary government, vociferous women of the time were silenced by both the guillotine and public denunciation. Head officials often belittled the civil desires of women and considered their pleas as “…horrible, contrary to all the laws of nature,” [Document 7]. Shortly after, the revolutionary government outlawed all women’s political clubs, reasoning them to be the cause of several altercations. Additionally, admirable female leaders were put imprisoned, beaten, and executed as a means to quiet female raucousness. Mericourt was eventually flogged and placed in a mental asylum and Olympe de Gouges along with numerous other women was executed by guillotine during the Reign of Terror [Document 9]. In many ways the catastrophic downturn of the women’s revolutionary movement reflected the growing discomfort for female political involvement. Male officials hidden behind official regulation, which validated execution and imprisonment, wanted to discourage female proclamation and subsequent influence.

Although the women of the French Revolution did not gain the right to vote or hold office, they had certainly broken free of conventional conformities. By diligently participating in the French Revolution, in support of both gender rights and political principle, women had assumed a public role in French society. While the influences of male suppression had quelled the reams of female protest, women had come to recognize the importance of their status amongst men at the close of the 18th century.